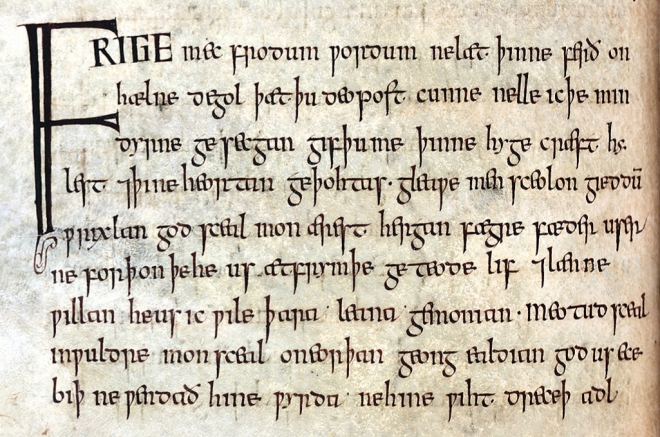

A foolish notion. What would it be to translate not only for meaning, what we usually mean by “meaning,” reference, signification, the pointy ends of words, but also for everything else about, within, around them: their loops and curls, textures of their paper, sleepiness of the scribe, slips in the book’s stitching, burn marks at the edges of pages, how a sequence of ascenders and descenders read as skyline or script for a roller coaster.

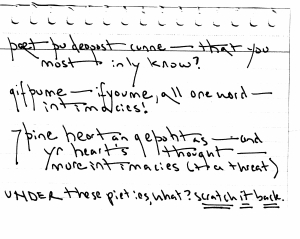

Crazy yeah. But if (1) you’ve come to feel translation’s originary no matter what, and (2) your semantic translation of a poem has sucked no matter what, and (3) you’re not done with said poem, and (4) you have a decorative itch – well, you might come round to a like crazy. You might start to wonder if þine heortan geþohtas, the force of your heart’s thought, might be most truly got not via narrowly focused semantic emissions, but through a sprawling heterogeneous relation of potentially everything in the nexus of poet poem scribe translator reader annotator and medium.

Semantic reference is a span of human meaning about as sliver as visible light is to the electromagnetic spectrum.

My guiding thought in Overject has become, assume you know nothing about what should or shouldn’t be translated.

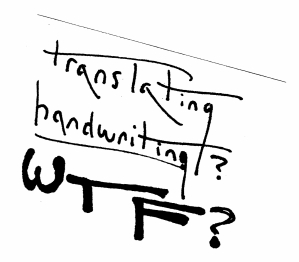

My guiding thought in Overject has become, assume you know nothing about what should or shouldn’t be translated.  Feel like translating handwriting? Translate handwriting. Feel like transmitting hesitation? Transmit hesitation. Anything honest in the encounter between old damaged minor text and ignorant inexpert minor reader’s fair game.

Feel like translating handwriting? Translate handwriting. Feel like transmitting hesitation? Transmit hesitation. Anything honest in the encounter between old damaged minor text and ignorant inexpert minor reader’s fair game.

Now if at every point everything is open to translation – how do you decide? I’ve found me guided by intuition and accident.

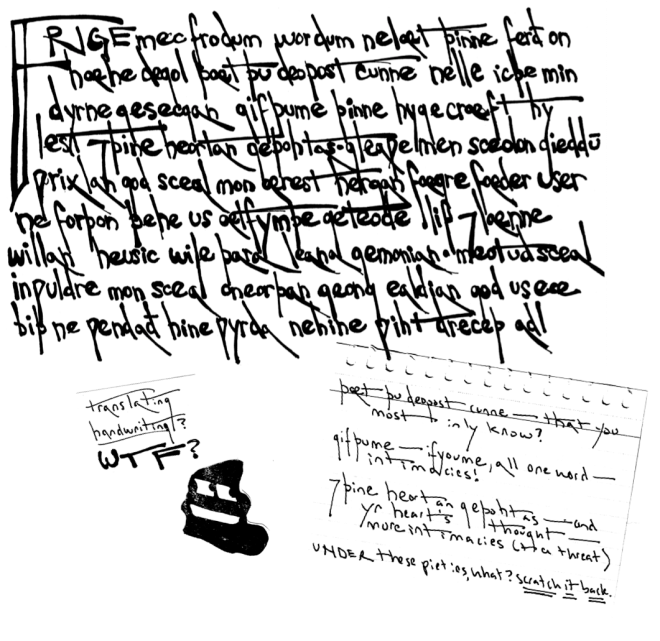

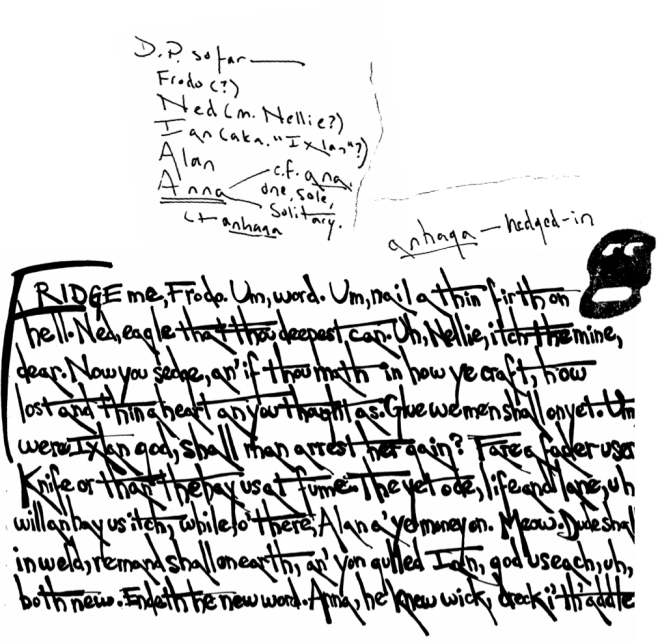

Gut, and happenstance. Who have led me to handwriting. My work with which in Dumuzi had drawn me to more exuberant organic loops and sweeps than the hell scraps there could suit. Into Overject went the overflow. And the self-indulgence of translating nothing but handwriting pushed up in me little spikelets of self-doubt. And one of those has made it to a post-it.

And the possibility of annotating my translations bloomed hard and fast in my head and the next flower was a notecard on which I found a bit of semantic translation wanted (musewise, it wasn’t I who wanted, but just who let it) to burst in. And these three – transcription, post-it, notecard – plus a ghost face who poked in from a later page, became assemblage.

And the possibility of annotating my translations bloomed hard and fast in my head and the next flower was a notecard on which I found a bit of semantic translation wanted (musewise, it wasn’t I who wanted, but just who let it) to burst in. And these three – transcription, post-it, notecard – plus a ghost face who poked in from a later page, became assemblage.

The next major adventure is homophonic translation, of which I’ve written before. Here too annotation and anima. (The abrupt edge on the right is a scanner error. Not all accident is welcome.)

“D.P.” = Dramatis Personae. One way I hope to make this work a little less esoteric in the end is, draw names out of the sonic surround, faces out of the visual noise, and see what storylines they hint at (no more, dear hearts, than that).

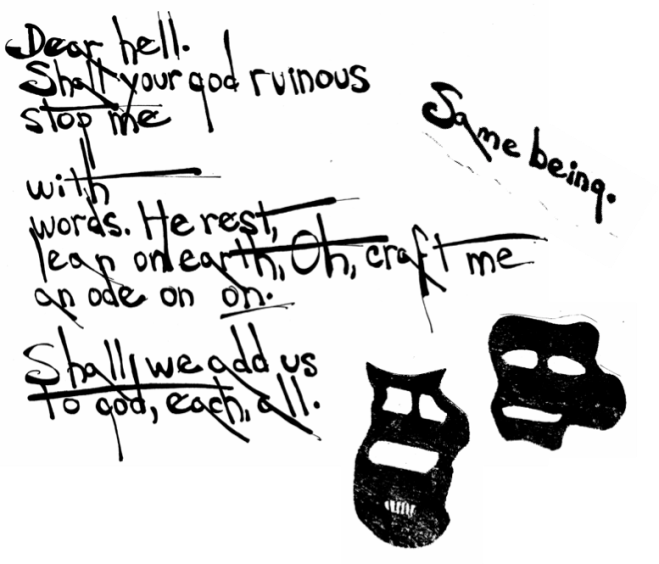

Oh now the lure of semiosis. Not from the meanings of the “original poem.” Rather from the nexus formed when that poem’s meanings intersect with recent homophonic accidents and my momentary interior weather and demonic images yet to be actualized. An ambivalent compound arises.

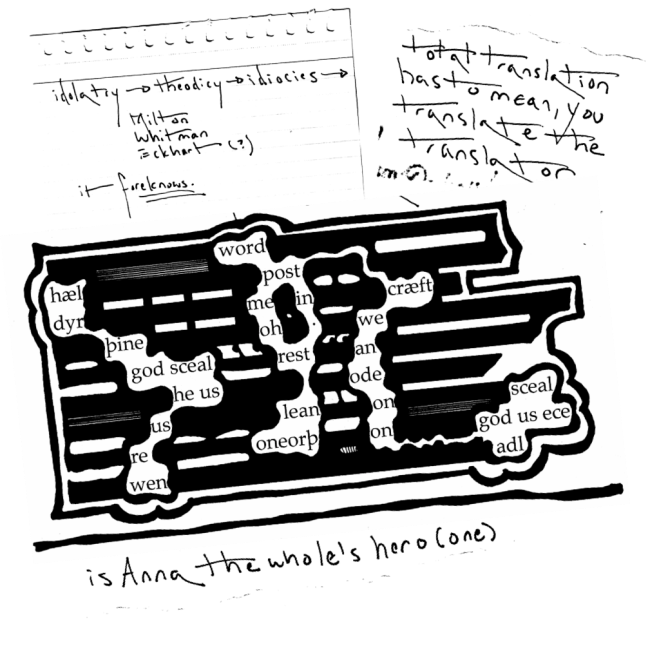

Comes now a grave move. So much is lost in this moment! The haecceity, the suchness, of each t, each l, each g, unlike any other anywhere in existence, all now made to be of a same sameness.

I take the manuscript page and I type it up.

I try to make up the loss. I follow the leads of ascenders and descenders. After selecting some text, à la Phillips, I black out the remainder with a Sharpie. The thickness of the erasure line is governed by the heights and depths to which the line (or portion thereof) reaches. No ascender? It thins. No descender either? That thins it further. One et (⁊) and it goes down a long way. One thorn (þ) and it reaches both high and low.

The whole of the rest of the design, mouths and eyes, windows and doors, lions and tigers and heroes and hydras, or here a school bus climbing a hill, is begun from the thicks and thins of the bars, and the white slits left between.

The chosen text has the quality of a code. As if a minor character in Beowulf had got his hands on an Enigma machine. Crypto-crisis. So I put on my tinfoil Turing cap and coughed up this.

And when I got to that, I felt I was an inch or two closer, maybe not more, to a true translation of folio 88V of the Exeter Book.

Closer anyway than my semantic translation of that folio, which I did some years ago, and goes like this.

Ask me straight out. Don’t hide your whole life

what only you know. I won’t tell you what matters

if you hold the force of the heart of your thought back.

The wise work in riddles, praise God foremost,

our Father who said of His Creation we could

live here a while, a gift he’d remind us of.

In glory Measurer, on earth humankind,

young here is old, God is eternal with us,

events don’t touch Him, illness

You can hear the strain in it. Couldn’t care less about these pieties. Why’s the poem compel me at all? Nothing in its answers speaks to me. The pressure I hear in its questions – in the failure of its answers to relieve the pressure – that moves me.

Around here I realized two things. One, my epigraph, it spoke to me out of Job, “Where shall wisdom be found?” Is that what I’m translating, the Exeter poet asking it, into me asking it?

Other is, the work has to be in earnest. I can fuck around as much as I like, goof off, poke fun, mess shit up, that’s fine, but the asking has to be in earnest, otherwise this’ll be a dumb game I’m sick of real soon. Flip side, as long as it’s for heartfelt for me, it can be totally way goofball, and still live, short I and long.

Really exciting stuff, Chris. Rather than making me feel I’m only scratching the surface when I write/adapt (which it also does), it inspires me to go wilder and deeper. And you’re so clear about the how of it that any teacher, having prepped the class for an open-minded approach, could use this. Of course, no one could get there in a day, a week, even a term, but the encouragement is there. Might be interesting to talk at some point about the role of time in the process. It’s not always clear — even to me, who heard about a lot of this while it was going on — what the timeframe is like. How long the hesitations were, even how long it would take you to do your thing with the Sharpie.

LikeLike

Yeah, you’re right to ask about chronology, because I’ve left a lot out. Basically, before the two Great Pivots – handwriting, annotation – a rough draft of the thing unfolded slowly and in a very different order.

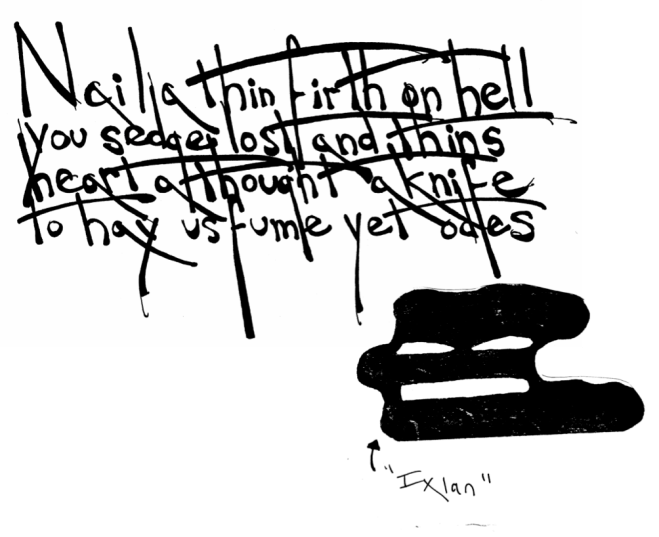

First was a semantic translation I couldn’t get right. Next, an erasure/treatment of that translation. I liked that but it felt pretty derivative on its own. Next, a homophonic translation. Liked that too but again kind of been done to death. Then an erasure/treatment of a diplomatic transcription – the school bus image, basically. That felt newer but also esoteric as all hell. Then a distillation from the homophonic translation – what’s become the “Nail a thin firth” poem.

These formed fitfully over a couple of years. All laserprint and Sharpie – no handwriting, no scraps. Bundled it together, with a long abstruse afterword, sent it out a couple places and sort of forgot about it. When I did revisit it, something felt off about it, imaginatively incomplete.

When Dumuzi gave me handwriting and collage, the missing practices were suddenly not missing, and kind of over a period of a few days I saw what I’d been up to with Overject all along: a translation in which everything is open to transmission and metamorphosis. Handwriting and annotation are the tangible immediacies that realized that for me.

So there’s a fiction here. I say everything is up for grabs, but I’ve sketched out the paths of translation already. And yet I don’t feel I’m fibbing. I’m redoing what I’ve done before, but it also feels new in the doing of it, and I’m ready for it to change direction at any moment.

Writing about it yesterday here, when I got to the epigraph from Job, and I wrote, “‘Where shall wisdom be found?’ Is that what I’m translating, the Exeter poet asking it, into me asking it?” that was an AHA for me, right then, typing that in. As long as I’m having those aha’s, I’m good with saying, this work is new work.

I have maybe a peculiar understanding of Pound’s MAKE IT NEW. I feel you can do something a thousand thousand times and still have it new that millionth and first time. The obverse is true too of course. Smart phones.

Thanks for your thoughts. Real incisive. Oh, and as to your last question, how long the Sharpie work takes, 9 or 10 lines like “Frige mec frodum” would take 2 or 3 hours. The school bus image, half a day, once I’ve designed it. The scraps, 15 to 45 seconds!

LikeLike